The Eighth and Ninth Plagues: A Theological and Historical Analysis of Exodus 10

The book of Exodus is one of the most significant narratives in the Bible, chronicling the deliverance of Israel from Egyptian bondage through a series of divine judgments upon Pharaoh and his people. In Exodus 10, we encounter the eighth and ninth plagues—locusts and darkness—both of which play a critical role in the escalating confrontation between God and Pharaoh. This chapter is not merely an account of supernatural events but a profound theological statement about divine sovereignty, human rebellion, and redemptive history.

I. Context and Structure of Exodus 10

Before analyzing the specific plagues, it is crucial to understand the broader context of Exodus 10. The plagues serve as a divine confrontation between Yahweh and the gods of Egypt, demonstrating God’s supreme authority over creation and history.

The structure of the plagues follows a pattern of increasing intensity:

1. The first three plagues (blood, frogs, and gnats) are nuisances.

2. The next three (flies, livestock disease, and boils) escalate in severity.

3. The final four (hail, locusts, darkness, and the death of the firstborn) are catastrophic and directly challenge Pharaoh’s perceived divine status.

Exodus 10 falls into this climactic phase, where God is no longer simply afflicting Egypt but dismantling its economy, society, and religious structures.

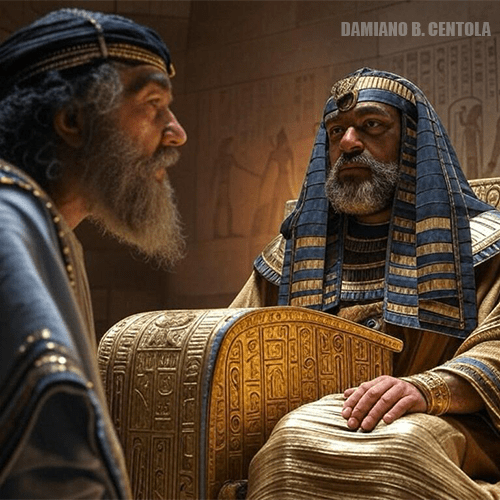

II. The Eighth Plague: Locusts (Exodus 10:1–20)

A. Divine Purpose in Hardening Pharaoh’s Heart

The chapter begins with a divine declaration:

“Then the LORD said to Moses, ‘Go to Pharaoh, for I have hardened his heart and the hearts of his officials so that I may perform these signs of mine among them, that you may tell your children and grandchildren how I dealt harshly with the Egyptians and how I performed my signs among them, and that you may know that I am the LORD’” (Exodus 10:1–2, NIV).

This passage raises a significant theological issue: divine hardening. The hardening of Pharaoh’s heart has been a recurring theme in the plagues, but here, God explicitly states its purpose—not only as judgment upon Egypt but as a means of solidifying Israel’s historical memory.

By allowing Pharaoh to persist in his rebellion, God magnifies His glory through judgment, ensuring that Israel will recount these events for generations. This aligns with a biblical motif where God uses the resistance of rulers (e.g., Nebuchadnezzar in Daniel 4) to display His power.

B. The Warning to Pharaoh

Moses and Aaron deliver a stern warning:

“If you refuse to let my people go, I will bring locusts into your country tomorrow. They will cover the face of the ground so that it cannot be seen. They will devour what little you have left after the hail, including every tree that is growing in your fields” (Exodus 10:4–5).

The specificity of the warning emphasizes both divine foreknowledge and Pharaoh’s culpability. Unlike previous plagues, which caused partial destruction, the locusts threaten to consume everything. This represents an economic collapse, as Egypt depended heavily on agriculture.

C. Pharaoh’s Officials Begin to Falter

For the first time, Pharaoh’s officials intervene:

“Pharaoh’s officials said to him, ‘How long will this man be a snare to us? Let the people go so that they may worship the LORD their God. Do you not yet realize that Egypt is ruined?’” (Exodus 10:7).

This marks a shift in internal Egyptian politics. Pharaoh’s advisors recognize that continued resistance is irrational, suggesting growing division within his court. Their words—“Do you not yet realize that Egypt is ruined?”—are significant. They acknowledge the nation’s collapse, yet Pharaoh remains obstinate.

D. Pharaoh’s Negotiation and God’s Judgment

Pharaoh, under pressure, attempts a compromise:

“Moses and Aaron were brought back to Pharaoh. ‘Go, worship the LORD your God,’ he said. ‘But tell me who will be going.’” (Exodus 10:8).

Pharaoh’s insistence on limiting Israel’s departure reveals his underlying fear: If entire families leave, they may never return. Moses rejects this, affirming that worship must involve all of Israel, including their livestock. This theological point highlights that true worship requires total commitment, not half-measures.

Enraged, Pharaoh expels Moses and Aaron, prompting immediate divine action:

“So Moses stretched out his staff over Egypt, and the LORD made an east wind blow across the land all that day and all that night. By morning the wind had brought the locusts” (Exodus 10:13).

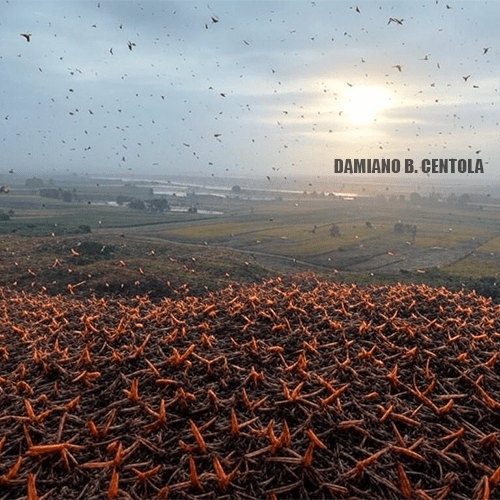

The description of the locusts emphasizes their overwhelming numbers:

“They covered all the ground until it was black. They devoured all that was left after the hail—everything growing in the fields and the fruit on the trees. Nothing green remained on tree or plant in all the land of Egypt” (Exodus 10:15).

This parallels Joel 1:4, where locusts symbolize divine judgment. The devastation leaves Egypt on the brink of famine.

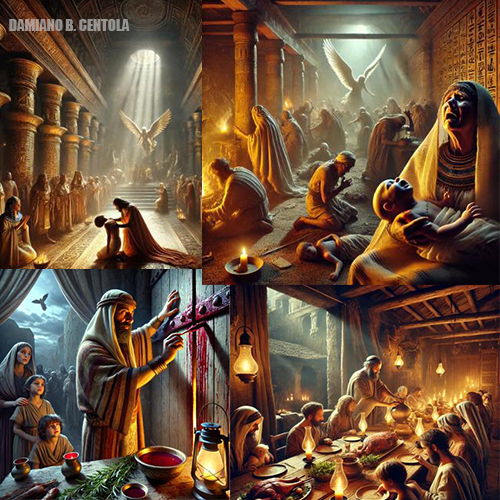

E. Pharaoh’s False Repentance

In desperation, Pharaoh summons Moses:

“ ‘I have sinned against the LORD your God and against you. Now forgive my sin once more and pray to the LORD your God to take this deadly plague away from me’” (Exodus 10:16–17).

This confession, though seemingly genuine, is short-lived. Moses prays, and a west wind drives the locusts into the Red Sea. However:

“But the LORD hardened Pharaoh’s heart, and he would not let the Israelites go” (Exodus 10:20).

Pharaoh’s repentance is superficial—he acknowledges sin but refuses to change. This demonstrates the difference between remorse and repentance.